La Yunko Makes History

Tags

"When I dance I feel that the singing or the guitar enters my body directly through the skin and, as it reaches the depths of the body, like a cell, that's where I feel my dance comes from"

—Junko Hagiwara, La Yunko

In August, 2024, Junko Hagiwara "La Yunko" became the first non-Spanish dancer to win the most coveted prize in flamenco dance: El Desplante, awarded by the International Cante de las Minas Festival. At first, the achievement was clouded when the artist went on stage to collect her statuette and received boos from the audience. Being a trailblazer is no easy feat. La Yunko continues to face some backlash for winning such an esteemed prize in the flamenco world. "There were moments when I sank, I hid any comments on social networks, but sometimes they reached me accidentally. At that moment I was sinking." But resilience won. "At the same time, since I receive so many messages of love and support, I appreciate it and it surprises me a lot. That becomes a very big strength for me to move forward. I feel very happy apart from having such an important award and with a lot of responsibility." As Yunko told El País:

“When I dance, I don’t know where I’m from—whether I’m from Japan or anywhere else. I just dance, and that’s it.”

Flamenco, Japan, and the International Stage

From the outside, it might seem striking that in Japan there is so much interest in flamenco. So much so that it is considered the "second homeland of flamenco." The cultural exchange between Spain and Japan around flamenco stretches back nearly a century. The earliest documented contact occurred in 1929, when the famed Spanish dancer Antonia Mercé, "La Argentina," toured Tokyo during her international engagements, introducing Japanese audiences to flamenco performance. Shortly after, in 1932, the Spanish guitar was heard for the first time in Japan, with Carlos Montoya accompanying Teresina Boronat.

Although flamenco’s presence in Japan subsided during World War II, it resurfaced in the early 1950s with a diplomatic touring performance by flamenco singer Rafael Romero “el Gallina,” whose quejíos (painful vocal expressions) were instrumental in sparking renewed interest among Japanese audiences. The 1960s were a formative period for Japanese flamenco, coinciding with Japan’s post-war modernization and cultural openness. Tours by luminaries like Antonio Gades and Pilar López and the popularity of the film Tarantos (1963), featuring Carmen Amaya, deepened the fascination with flamenco. In 1967, El Flamenco, an iconic tablao in Tokyo, was established and became the primary stage for Spanish artists touring Japan, helping transform the local interest into a more structured community.

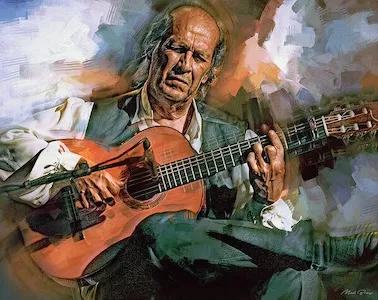

During this era, numerous Japanese dancers and performers traveled to Spain (particularly Madrid and Seville) to immerse themselves in flamenco’s source culture. Groundbreakers like Yasuko Nagamine and Yoko Komatsubara studied and performed at traditional venues such as the iconic Tablao Los Gallos, while influential figures such as Shōji Kojima (who arrived in Spain in the mid-1960s and trained at the famed Amor de Dios studio) later returned to Japan, founded schools, and nurtured flamenco’s growth domestically. Throughout the 1970s to the 1990s, flamenco in Japan matured into a strong cultural presence. Spanish performers like Manolete, Tomás de Madrid, and Paco de Lucía toured extensively, attracting audiences and inspiring Japanese dancers.

By the early 21st century, the relationship had grown into a sustained transnational practice. In his book Un tablao en otro mundo, Journalist David López Canales writes: “For decades, guitarists and dancers have studied and trained to bring flamenco in Japan to a level that many Spanish artists openly admit is now comparable to that in Spain.” According to a 2020 study, Japan was home to 500 flamenco academies, and 80,000 Japanese people, the majority women, were learning flamenco. This means that Japan now has more flamenco academies than Spain itself.

Flamenco has a unique power to build cultural bridges because it speaks directly through emotion, rhythm, and the body. Though deeply tied to its Andalusian origins, its themes of struggle, longing, and joy are universally understood, allowing audiences across the world to connect with it on a human level. As flamenco has traveled beyond Spain, it has become a shared cultural language—one that invites learning, respect, and exchange rather than imitation. In this way, flamenco shows how art can transcend borders, transforming tradition into a meeting place between cultures.

Works Cited/Further Reading

- https://www.elmundo.es/cronica/2024/09/12/66d9cde7e4d4d847238b45a7.html

- https://quepasamedia.com/noticias/entretenimiento/una-bailaora-japonesa-se-alza-con-uno-de-los-premios-mas-prestigiosos-del-flamenco-espanol/

- The Inexplicable and Established Bond Between Flamenco and Japan by Tablao de Carmen

- Header Image: Angélica Reinosa y Antonio Heredia por El Mundo

- Image Gallery: La Yunko en Festival Internacional del Cante de las Minas de La Unión (Murcia) por Marcial Guillén (EFE) El País; Angélica Reinosa y Antonio Heredia por El Mundo

SUPPORT

Ignite the transformative power of flamenco for all.

100% of your donation goes directly to artists and programs.

Your support makes all the difference.

.png)

.png)

.png)